Dust Collisions & Growth#

Review: [Birnstiel et al., 2016]

Growth mechanism#

When Temperature inside PPD has decreased sub-micrometer to micrometer sized solid particles start to condense

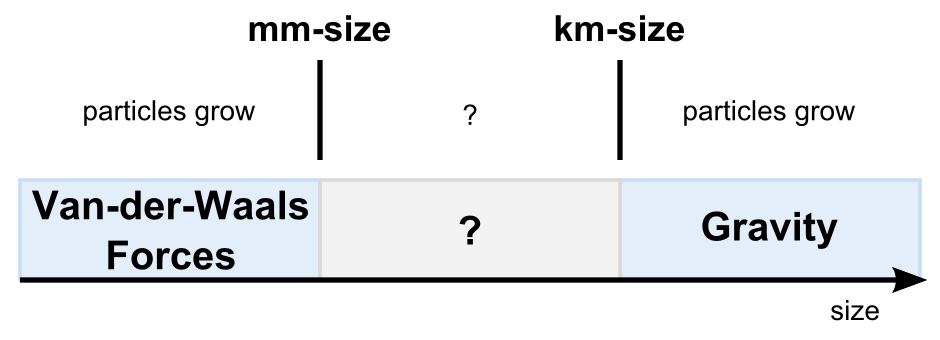

Particles are coupled to the gas (Orbiting at Keplerian speed) and this is what drives the relative speed of µm dust grains (ie more or less head wind relative to their size). Dust orbits the protostar at very high velocities but the relative velocities between particles in collisions can be very slow (few cm or a few mm per second). At such velocities a “bouncing barrier” exists [Zsom et al., 2010]. Up to mm sizes the sticking is dominated by Van der Waals type forces, leading to the formation of fluffy aggregates. Past the km scale, gravity dominates [Güttler et al., 2010].

» Coagulation of dust and ice particles #

Nomenclature (from ref 2)

Grains(dust or ice) or sub µm in size and homogeneous in composition (1 material) - (Not really accurate is it ?)Agglomeratesare grains that can be heterogeneous in compositionPebblesmm to decimeter sized porous agglomerates (up to growth barrier when hit and stick regime stops)

Fig. 35 source: Formation of comets Blum 2022 - to reproduce better#

The Bouncing Barrier#

Can the Bouncing barrier be beneficial to growth ?

Formation of planetesimals from pebbles#

via streaming instability and subsequent gravitational collapse

Dust settling#

Streaming Instability#

Gravitational collapse#

Evolutionary alteration#

Leads to 3 different categories of evolved planetesimals

Icy pebble pilesIcy rubble / pebble pilesNon icy rubble pilesThey can be further subdivided depending on the evolution process

Experiments#

» Overview #

Note

Insert Blum review paper

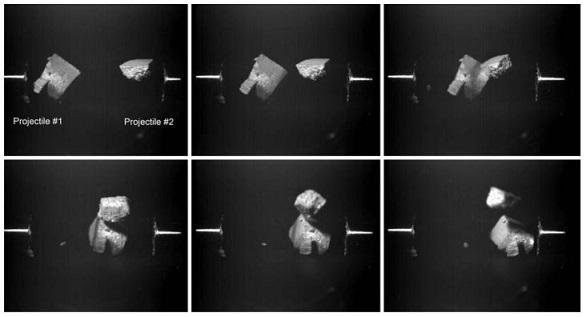

Find and put collision videos

To understand how planet forms we need to perform some collision experiments

Fig. 39 source:#

» Important parameters #

Size of objects colliding #

Explanation

Van der Walls forces when small particles

Gravity past km size body

What is happening in the middle ?

Fig. 40 source:#

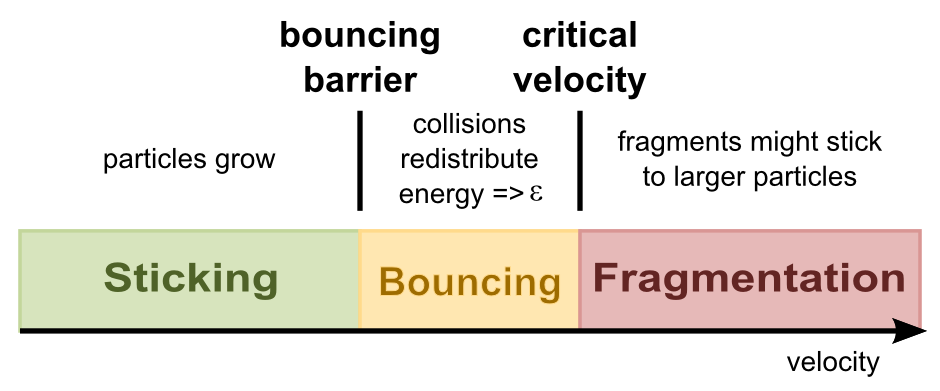

Speed of colliding objects #

Although the dust orbits the protostar at very high velocities (cf previous chapter), the relative dust velocities in collisions can be very slow – in the order of a few cm or a few mm per second at the earliest stages of planet growth.

Fig. 41 source:#

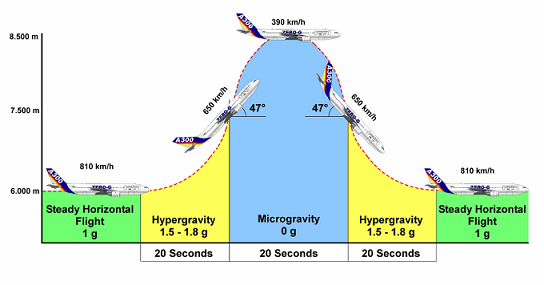

Microgravity#

To reach low velocity collision experiments needs to be performed in microgravity

What collision speed can be achieved

Fig. 42 source:#

Nature/Structure of the colliding object #

In the laboratory, a plethora of collision experiments have been conducted which clearly define the sticking bouncing and fragmentation regimes for small dusty particles at low velocities [Blum, 2010]. Those experiments, carried out with different dust composition (SiO2 / Carbon dust), have shown that in “pure dust” collisions, the dust material is less important than the grain size, the surface roughness and porosity.

All of those could be investigated by SEM

Lab is often in microgravity to reach low velocity while avoiding sedimentation [Blum and Wurm, 2000]

The outcomes of these collisions provide vital data to modellers who want to understand how collision properties and outcomes impact the broader processes of planet formation. [23]

Bouncing barrier#

Those two figures comes from [Testi et al., 2014]

models of grain growth

Alongside the size of the colliding particles the relative velocity is also important

» Icy particles collision #

We know that in protoplanetary disks both crystalline [Terada and Tokunaga, 2012] and amorphous [Smith et al., 1989] ice-coated dust grains are present at and beyond the snow line. However, whilst the amorphous icy layers predominantly are formed in pre-stellar cores via chemical vapour deposition, we now know that most of this chemical “knowledge” is lost as star formation progresses, and consequently by the time icy grains are incorporated into planet-forming disks around newly formed stars, the icy material has been desorbed, processed and re-adsorbed possibly several times citation to extract. Therefore, the most representative amorphous ices of planet-forming icy grains are vapour deposited ASW [Aikawa et al., 2012]

Note

What is difference between chemical vapour deposition and vapour deposition

Aikawa 2012 may not be a good ref, check Deuterium fractionation papers

Ice collision properties#

Ice enhnaces the stickiness of interstellar grains [Gundlach and Blum, 2015]. No collisions between amorphous ice particles has been performed to date (even though they are present in PPD), the reason being the complex and metastable nature of amorphous ice which makes it difficult to produce, store and use. This is what I was trying to solve

Note

Extract ice figure

cite Neutron data above with this paper

The difference between Ice and Dust#

Note

insert Wang 2008 pictures

HGW ice grains#

I designed an experiment to produce Amorphous Ice grain analogues. HGW is similar to ASW.

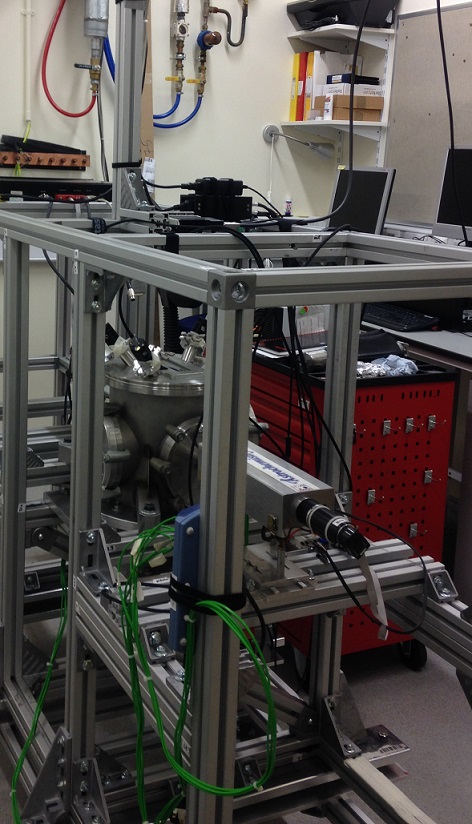

The microgravity Ice collision experiments at the OU#

Note

Insert barillet photo in the paper

Fig. 45 source:#

Comments#